Does feminism need rebranding?

Feminists whine, feminists hate men, and feminists are sour, humourless, and always mad. These are just some of the prejudices that are still very much alive in society today. And they certainly make women think twice before they call themselves feminists. But what exactly is feminism? What have these women achieved in the past? Does the movement need re-branding?

What’s feminism?

Those who thought that feminism began with the fight for the contraceptive pill were deceived. Feminism is an international movement that has been striving for an equal position for women for over 200 years. Whether it’s about suffrage, equal wages, the right to contraception and abortion, or addressing sexual harassment: as a feminist, you criticise the unequal power relationship between men and women, and you fight to change it. The goal of feminism is for women to have the same opportunities as men: economically, politically, and socially.

Waves

As a movement, feminism stems from the values of the Enlightenment. When the first Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was drawn up in 1789, it inspired marginalised groups within society to demand their rights too, just like the revolutionary slogan “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”. Emancipatory movements for democrats, Christians, and the enslaved shot up like mushrooms, as did the then still very young feminist movement.

Three years later, Mary Wollstonecraft wrote the book “Plea for Women’s Rights”, and from that moment, things started to develop quickly. Over the past centuries, feminism has developed into an interplay of social movements. At times they built on each other, while at other times they approached things completely differently. That’s why fragmentation remains common, as feminism tends to appear in waves. In this sense, feminism is a steady and continuous revolution: from the first, second, and third waves, to the fourth one in which we are now.

First wave of feminism (1850 – 1920)

Compared to the illustrious second wave, we generally don’t know as much about the first wave. We all know the images of bare-chested women fighting for the right to abortion, but we often don’t realise that their predecessors fought for almost 70 years for things that we now take for granted. Think of our voting rights, the right to education, and the right to own property, go to work and earn our own income. Many of the feminist themes from the pioneering years form the basis of our society today.

Insignificant beings

These first feminists lived in a time when women were invariably kept in their place by a society that was steered by ecclesiastical views on the position of women. The image of women was traditional, and considered women as the person behind the pots and pans and tasked with bringing as many babies into the world as possible. Women were seen as insignificant beings, intellectually and emotionally less capable, and less stable than their male counterparts.

Although women were generally not allowed to work, this changed during the Industrial Revolution. Women from the lower classes went to work outside the home as maids and factory workers. During WWI, the number of female workers increased even more. As men were fighting at the front, women took over the work in the factories and on the farms. They earned their own income, but they were still not allowed to vote. The realisation dawned that political participation was also essential for women.

Black women

In the United States, the feminist movement blended with abolitionism, the movement that fought for the abolition of slavery. In 1848, some 200 women gathered in a New York church to discuss the social, civil, and religious rights of women. The right to vote was first put on the table at that Seneca Falls Convention. The convention was organised by two white, female abolitionists who had been barred from a convention against slavery because they were female.

While black women also took an active part in the work of the American women’s movement, it eventually became a movement for white women. Ironically, in 1870, the right of black men to vote created a huge stir within the abolitionist-led women’s movement. “Will women truly get to vote later than black men? Then we might as well all have been born on a plantation,” wrote a white woman in Revolution, the newspaper of the movement. From then on, black women were forced to walk behind white women in demonstrations, or worse: they were often not even allowed to participate.

Voting rights at last

The struggle of American and European suffragettes was fierce and persistent. As they marched for the right to vote, they were mocked, beaten, and arrested. However, in 1919, the time finally came and women were allowed to go to the polls. Universal suffrage was the greatest achievement of the first wave. After that, individual groups continued to fight for contraception, equal education, the right to work, and the right of black women to vote. The latter took several years in various countries: for example, it wasn’t until 1965 that the first black woman in America was allowed to vote.

Throughout all of these developments, the movement as a whole became fragmented. There was no longer a unified goal to strive for and the position of women quietly moved along, without any significant changes or improvements. In the 1950s, the traditional image of women was once again the most common perspective. Until the turbulent 60s.

Second wave of feminism (1965 – 1985)

The second wave was a direct reaction to the position of women from the 1950s. While women had acquired the right to vote, progress in the field of work was not as rosy. Women were still bound to being housewives. They had no other purpose in life except to keep house and look after their children. Many women felt empty, tired, and unfulfilled, and they desperately wanted to break out of their suppressed existence.

In the United States, this dissatisfaction among women was called “the housewife syndrome”. Many women felt aimless and hopeless. In 1963, Betty Friedan wrote the book The feminine mystique, which became an international promoter of the second feminist wave. Women everywhere started to speak out, giving sex education and setting up discussion groups. With the advent of the contraceptive pill in the early 1960s, they also became partially in charge of their own bodies. The advent of contraception brought enormous freedom. A new world was on the horizon.

Women’s cafés

Soon, attention turned to inequality of women in all kinds of areas. “What’s personal became political”, was the Dutch feminists’ slogan. The women of the second wave were not only fighting for the right to paid work, but also for attention to domestic violence and the unequal distribution of care responsibilities. They took to the streets for the right to abortion and for social and sexual freedom. The second wave was a broad movement with wide-ranging themes, but they were all connected by a common aspiration: equality between men and women.

Gradually, this wave also fragmented. Where there previously was fierce activism, women now retreated into discussion groups. Women declared their solidarity with other women, and this manifested itself in special women’s spaces where men weren’t welcome. Women’s houses, women’s cafés and women’s housing groups popped up everywhere. Many feminists went their own way and started focusing on specific social and political themes, such as peace, abortion, racism, or lesbian love.

Post-feminism – the happy 90s

After the 1980s, when women stormed the shop floor in droves and abortion was finally legalised, feminism quieted down for a while. In the 1990s, the movement was even declared non-existent. Young women didn’t like the image of hairy armpits and thought that feminism was an outdated phenomenon. They preferred to associate themselves with the wildly popular concept of Girl Power and the idea that women should be sexy, assertive, and empowered. Throughout this optimistic time, feminism wasn’t seen as necessary anymore.

The girl power culture is often seen as a third wave, but secretly, the women of the 90s did nothing more than enjoy the achievements of the female champions of the waves before them. The 90s were not characterised by widespread protests, women did not jump onto the barricades, and there was no collective frustration about the unequal power relations between men and women. People simply thought that everything was fine as it was.

Political feminism? In these years, it seemed to be on the verge of dying out.

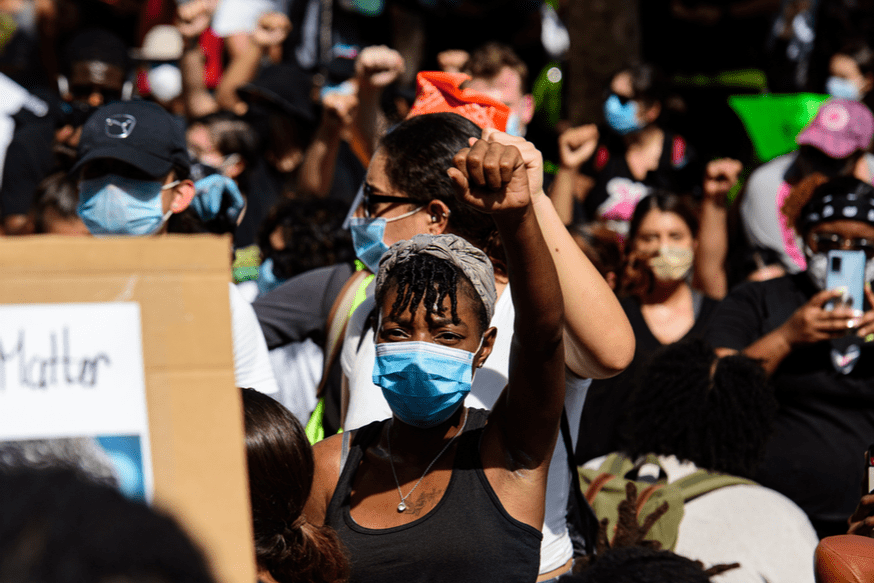

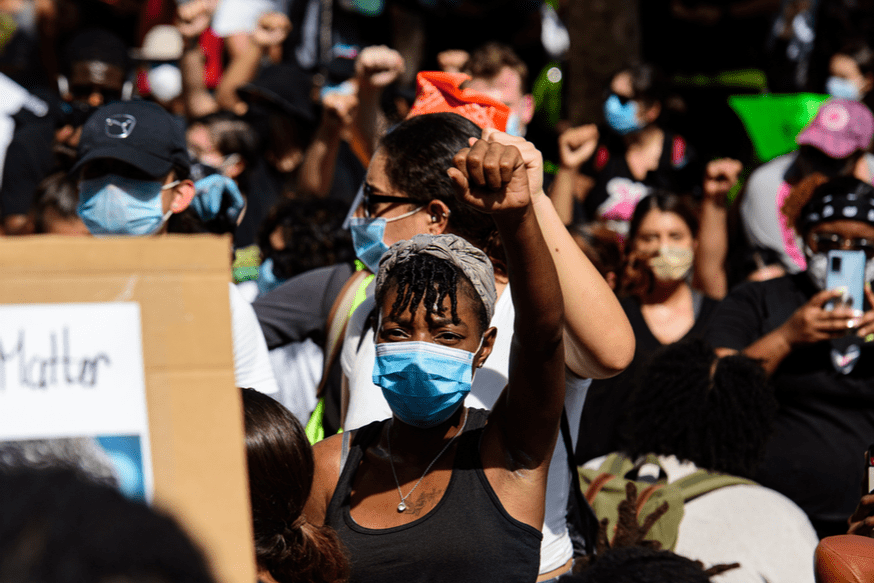

The fourth wave: sexism denounced

This brings us to the wave we’re in now, where social media has given women a huge platform to form a collective. The biggest issue? Men’s sexism towards women, which has been underplayed for years. The “naming and shaming” is a crucial part of this feminist revival, with women fighting to expose violence and sexism. In recent years, women have united in the MeToo movement, in the Women’s Marches against Trump, and in the FBrape campaign, forcing Facebook to acknowledge that they were not doing enough to keep sexism and verbal abuse off the platform.

Social media have proved to be a huge catalyst for this fourth wave, if only because dormant sexism has surfaced there openly. It’s quite a different thing to talk derogatorily about women in the local pub or football canteen than in a tweet shared by thousands online. Social media turned out to be not only a breeding ground for ideas and connection, but also a hotbed of shameless misogyny. So, feminism in this wave is no longer just about inequality, but also about raising social issues.

Ugly excesses

At the same time, many issues from the second wave remain unresolved. Gender inequality, for example, is still very much alive. Women still earn less for doing the same work, they’re still taken less seriously in boardrooms than their male colleagues, and they’re still attacked online. Whether you’re talking about the unfair distribution of care responsibilities, the representation of women in the media, or sexual violence and harassment, we’ve still got long way to go.

And that’s only mentioning the problems in the Western world. In many countries, your gender simply determines the rest of your life. Naturally, that life is a lot better when you’re a boy. Marriage, illegal abortions, female genital mutilation, and honour crimes: these are all ugly manifestations of misogyny which we in the privileged West don’t need to worry about.

Intersectional feminism

One of the pressing issues of the fourth wave is intersectionality: a concept closely related to the need to look beyond our western views. It’s a form of feminism that stands up for the rights of all women and takes into account the fact that women have different backgrounds, classes, ethnicities, and sexual orientations. It shows that a form of feminism that focuses on women in a general sense only works to the advantage of white, heterosexual, middle-class women.

Intersectional feminists assume that every woman is made up of different social strata. You can be white and Protestant, black and lesbian, or Latina and poor. After all, every woman is different. These overlapping identities influence the extent to which you experience exclusion and discrimination. It’s not difficult to imagine a black lesbian woman experiencing more sexism than a white heterosexual woman from a well-to-do family.

Abortion? Some women can’t even afford it

Looking through an intersectional lens, you’ll see how the different forms of inequality work together and reinforce each other. It’s a bit like how the feminists and the abolitionists of the first wave found each other in their deprived position, before racism came around again. Of course, it’s difficult to tackle all the injustices in the world under one banner, but it’s something that this movement believes we should strive for.

As an intersectional feminist, you’re not only concerned about breaking the glass ceiling, but also about the inadequate minimum wage for women in “lower-level” jobs. Not only do you defend the right to an abortion, but you’re also aware that many women cannot even afford such a procedure. Not only do feminists see these invisible women, they must also recognise that their relatively privileged demands are causing marginalised women to be pushed even further into the background, says Juliet Williams, a gender studies professor at UCLA.

Rebranding feminism?

So, is it necessary to give feminism a makeover? A rebranding, so that young women feel attracted to participate in the collective endeavour again? Probably not. Each generation has its own interpretation of feminism, and each generation shapes the movement and its views in its own way, along with the resources and channels they have access to at that time.

After all, feminism is alive and well, as we’ve clearly seen in recent years. We take to the streets, we create clever hashtags to provoke political and social debates, and we realise that feminism also needs more inclusiveness and diversity. Feminism is not dead, it’s more active than ever. And it’s a privilege to be able to learn from the achievements and mistakes of the feminists of the past.

A global movement that’s not only led by privileged women who have enough time and energy for the cause of women’s rights? A movement that opens the floodgates to women from all corners of society? That would be a huge step forward. But it doesn’t require a full rebranding strategy.

Respond or ask a question

0 comments